Mediating and Unifying Princesses

Prestigious Dignitaries Connecting Worlds

The rarity of the collection presented: geographically isolated in a rugged region, shaped by the turmoils of time. Art history has never brought together so many Ngon masks. The theme of femininity, the originality of the Kom kingdom, honors matriarchy and femininity.

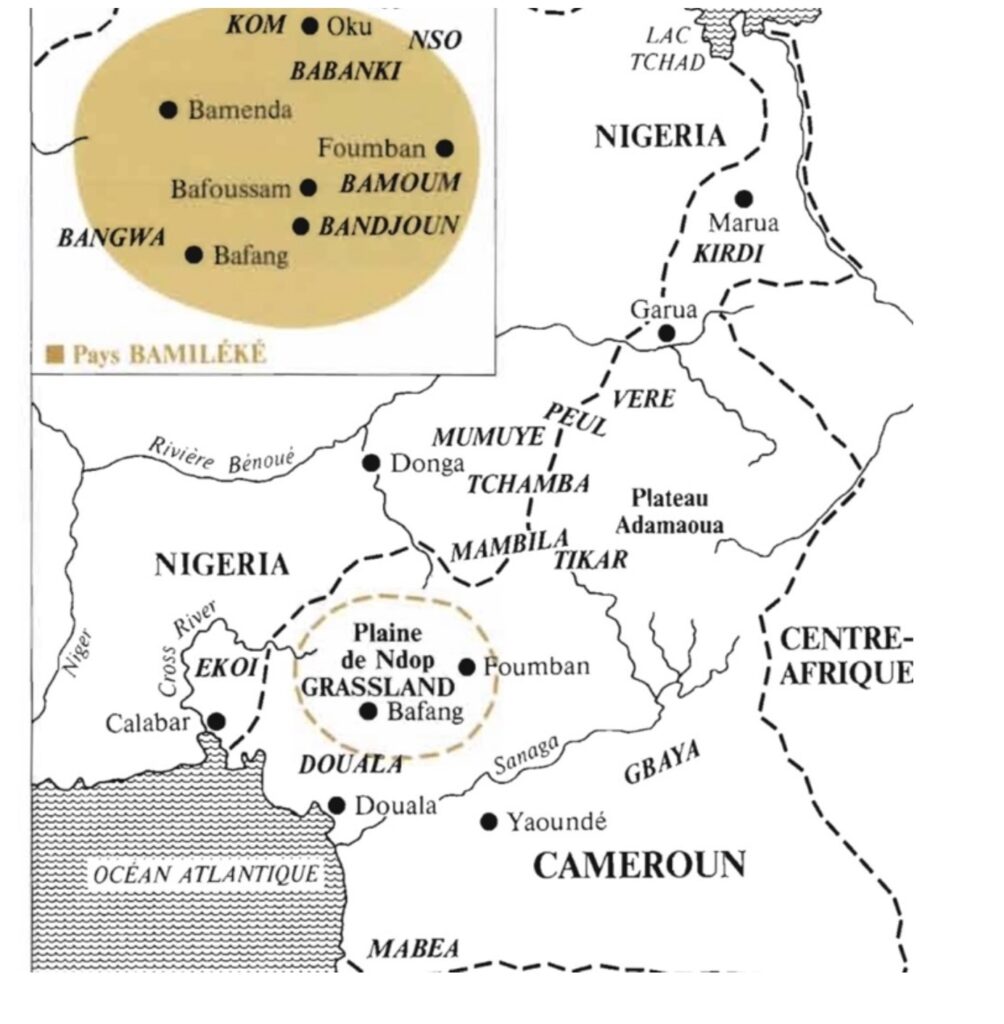

In the heart of the savanna of Cameroon’s volcanic highlands, located in the West of Cameroon and spanning the Northwest and West regions, lies the Grassland region. This area is home to five million inhabitants and is governed by skillfully organized chiefdoms, whose pre-established codes, structure, strength, and power resonate through art.

Art and power are intrinsically linked, with art serving as a testament to power, belief systems, and the importance of chiefdoms. This relationship is evident here at Brafa Art Fair in a unique and rare collection of Kom masks, called Ngon princesses. No previous exhibition has brought together these historical witnesses of idealized beauty and symbolism. These powerful aesthetic works, symbolically moving, come from the Kom kingdom.

Living and thriving in the Grassland region, the Kom kingdom stretches across the Northwest and is one of the largest kingdoms in the mountainous Northwest region, at the heart of the rolling hills of Bamenda.

Due to its geographically isolated and difficult-to-access location, the history of the Kom kingdom has faced challenges and upheavals over time, sometimes leading to the disappearance of these artifacts. No exhibition has ever gathered so many Bekom and Ngon masks. This collection is unique and rare, showcasing the inventiveness and expressiveness of the royalty, their beliefs, while also honoring the femininity of the princesses represented. The matriarchal Kom society, depicted through their idealized traits, and its beliefs are immortalized in these masks.

The Grassland region is politically and socially organized into around 200 independent and centralized chiefdoms. These princesses and their masks with powerful features symbolize the immutable legacy of kings and past kingdoms, reflecting a part of their history.

The unique collection presented here reflects the diversity and mastery of this art, known to us thanks to Dr. Harter, Louis Perrois, and Jean-Paul Notué.

Originating from the Grassland, encompassing the Bamileke people and including several kingdoms and chiefdoms such as Babanki, Bamoun, Bangwa, and Bandjoum, Kom’s artistic production is among the most renowned in the region. While the three extraordinary throne-statues are well-known, the princess masks remain lesser known, their representation often overlooked, and their meaning simplified. However, these superb young girl faces, called “Ngon” princesses, exude dignity.

They are multifaceted: princesses, mediators, witnesses to technical mastery of materials, inventiveness in artistic production, and acute stylistic sensibilities. These objects of power serve as protective links between the dead and the living, affirming the matriarchy of the Kom and the role of femininity within royalty.

Relationships Between Magical-Religious Beliefs and Artistic Representations: The Power of Ké as a Vital Force and the Fear of Ancestors

The Bamileke people believe in the existence of a supreme being, creator of the world. However, the spirits of the wilderness and family ancestors play a central role in their lives and beliefs. These three entities collectively form what is known to Cameroonians as “ké,” avatars of the vital force (Louis Perrois, Royal Arts of Cameroon, Musée Barbier Mueller, p. 13). A major characteristic of West Cameroonian culture is the belief in the actions of deceased ancestors, deeply influencing the living world.

Jean-Paul Notué, in his 1988 thesis on the symbolism of Bamileke arts, uncovered and analyzed the deep spirituality and sacred elements of western Cameroon, providing insights into the understanding of Ké through its celebrations and artistic creations.

Every Bamileke chiefdom is animated by the belief in ké, the vital force connecting the Creator, the environment, and the ancestors. Each chiefdom worships its own deity, as well as nature, rivers, rocks, and forests, which house local divinities to be honored and respected. The spirits of ancestors must not be defied or angered, as they are believed to be the source of societal misfortunes.

Ceremonies, rituals, and respectful attitudes are performed to appease the spirits of discontented deceased ancestors and counteract their malevolent actions, which are believed to cause misfortune, illness, and accidents.

The Importance of Princess Masks in the Kom

The emergence of Ngon princess masks in Kom rituals is of utmost significance. Through them, the cult of ancestors, the rebellion against death, the need for protection and power, and the mystery of fertility are all embodied.

These masks play a vital role in maintaining balance. They are danced during funeral ceremonies, belong to secret societies. Because of their sacred character, these mediating masks facilitate the passage of the deceased between worlds. They balance the power of ké to protect society.

Their voluminous, generous curves contrast with the profound weight of their crucial role for societal well-being. Their existence, rooted in their magical power and spirituality, links worlds and has profound implications. Their creation and the materials used are chosen and crafted following strict ritualistic rules. These masks, as sacred receptacles, are crafted under strict religious conditions to preserve their emanating power. The architecture of Kom society and artistic creation is based on belief in the power and reverence of Ké.

Society Socio-Cultural Structure: The Power of Ké in Grassland Governing Beliefs and Chiefdoms

Bernard Maillard, a Capuchin missionary who spent three years studying the Bamileke socio-religious structures on-site, wrote about his amazement at the admiration, fear, veneration, and awe inspired by the belief in Ké among the Bamileke.

The vital force of Ké was linked to both the dead and fertility. Celebrated every two years, its cult combined fertility rites for the land and people, initiation of young boys, and sacrifices meant to ward off malevolent forces threatening society. Honoring Ké through a 72-day ritual aimed at complete regeneration, the ceremony was rigorously structured. It included secret episodes reserved for initiates and large public gatherings to mobilize crowds, remind them of sacred beliefs forming the foundation of their society, and reinforce the codes of their spirituality.

During these rituals, Ngon princess masks appeared in funerary ceremonies, underscoring the importance of dignitaries who paid respectful homage to the power of ancestors. Due to their connection to femininity, it is likely that these masks were among the most closely guarded artifacts, occasionally displayed during Ké festivities for the public, including non-initiates, women, children, and outsiders.

The princess masks danced at funerals are also likely connected to secret societies concerned with vitality and regeneration.

The Role of Art: An Instrument of Structured, Hierarchical Social Organization

The authority of Ké is housed in the Fan, which holds its power and is transmitted through generations—except in Kom, a unique matriarchal society among the Bamileke. This exception of female-to-female authority transmission greatly elevates the significance of Ngon princess masks, which become sacred heirs of this vital force. As a result, these masks are rare and unique in the Grassland region.

These idealized princess masks are sacred heirs, mediators between worlds, and protective deities. They are the sole female masks in Cameroonian art to possess such powers and concentrate such spiritual force.

Gathered princesses, high dignitaries, and heirs of the queen-mother Mafo, who holds considerable authority (the king cannot contradict her), watch over, protect, and maintain balance.

Symbolic Description of Princess Masks

As the only feminine entities holding sacred powers and embodying the status of high dignitaries and mediators between worlds, the Ngon masks are rare and little-known. Yet, they represent the most beautiful artistic and symbolic expression of Cameroonian art.

The stylistic audacity of these masks conveys their significance through size and their profound symbolism through striking expressiveness. Their mastery of volume and modeling emphasizes the sensitivity they exude. Danced by men and worn atop the head like a helmet, the dancer’s face was concealed by a cloth to ensure the audience’s focus remained on the mask, intensifying its presence.

The generous curves and exaggerated dimensions of these princess faces are meant to unify the duality of worlds—between the living and the dead, past spirits, and future fertility. Their soft, flowing, and ample modeling promises fertility, wealth, and generational continuity, while their bowed forms demonstrate respect for Ké and the honored deceased.

Researchers and anthropologists primarily focus on the expressiveness and hairstyles of Ngon masks, often neglecting other features. This rare collection highlights variants in princely representations, particularly through distinctive hairstyles. Triangles and diamonds appear on their foreheads—geometric figures symbolizing strength, fertility, wealth, and femininity. These motifs dominate the ornamentation, creating a striking contrast between their rigorous lines and the generous roundness of their faces.

The open mouths with filed teeth, although symbolically significant, are often overlooked. J. Chevalier and A. Gheerbrandt explain: “The mouth is the opening through which breath, speech, and nourishment pass. It symbolizes the creative power of the soul’s insufflation.” (Dictionary of Symbols, p. 161). Thus, the mouth expresses the power of speech and mediation.

The eyes also stand out as an iconic feature. Intensified gazes, with almond-shaped or deeply worked pupils, are a hallmark of Bamileke style.

Materiality and Timelessness of Princess Masks

Beyond their captivating and powerful expressions, the materiality of the masks intrigues and invites closer inspection. From a distance, their surface appears uniform, but up close, it reveals irregularities that tell the story of Bamileke artistic genius. The passage of time has left marks on these faces, with layers and textures resembling the wrinkles of time itself. These “imperfections” humanize the idealized and sacred beauty of the princesses, almost rendering them alive despite their immortal essence.

The deep black patina of these masks resonates with their profound societal role and the sacredness they embody. This symbolism is reflected in the intensity of the black patina and its brilliance, which highlights the mask’s contours while magnifying its sacred spiritual purpose.

The courtly art, the princely confraternity art, the funerary art, the matrilineal art—all these rich, prestigious, and protective forms of mediating art—find their exceptional splendor in this unique collection.